.

.

Voyage dans la lune

.

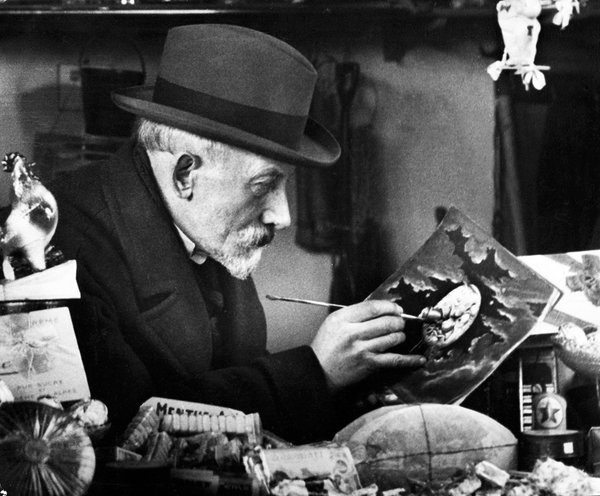

Director/Screenwriter/Actor: Georges Méliès

By Roderick Heath

On the 27th of December, 1895, Georges Méliès attended a special event arranged by the inventor brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. The brothers had recently perfected the machine they called the cinematograph—a creation that combined functions of moving picture camera, processor, and projector—and had been showing off the results around Paris throughout the later weeks of the year. On this night, they invited various showmen and theatrical impresarios to see the results of their labours. The invitees were to be one of the very first movie audiences, and at least one of them would soon become a pioneer of a new art. The Lumières had conflicting aims in the exhibition. They were exposing their creation and hoping to stir interest and publicity, which would help protect it from their many rivals, including Thomas Edison. But they also had avowed high-minded, scientific purpose for their invention on the cusp of dispatching a corps of photographers around the world to shoot documentary footage and exhibit the results. Méliès was an experienced stage illusionist who owned and managed the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, built by that famous magician. Méliès had become a success thanks to his meticulous attention to his theatre’s running and ingenuity in providing its attractions. Like all of the impresarios, he was transfixed by the new mode of communication the Lumières presented, and he jostled with the owner of the Folies Bergère in trying to buy their camera. But the brothers refused all offers.

.

.

Méliès got around this by travelling to London and purchasing another manufacturer’s projecting device, which he adapted into a noisy but working camera, at first directly copying the short films the Lumières had made and showing them in his theatre as a side attraction. Méliès discovered peculiarities in this new tool as he went along, as when his camera jammed whilst shooting a street scene. When filming was restarted, a moment of time had elapsed. When projected, Méliès saw the resulting jump and realised this basic quirk of the invention could be utilised to realise tricks similar to what he worked on stage. What was could suddenly become something else, only in the reality of film. Edison had already pulled a trick like this in one of his movies, but Méliès would make it the basis of a new expressive form. Méliès quickly found popularity with his new obsession far greater than what even his theatrical success could aspire to. He built a film studio in Montreuil, brought over his stock company of players, and began making movies with the verve and industry of someone who knew how to make and stage a show, as well as the quicksilver acumen required to adapt to a new medium. Most of his early works were only a few minutes long, but he tackled every subject he could, from ripped-from-the-headlines dramas like Divers at Work on the Wreck of the Maine (1898) and The Dreyfus Affair (1899), to titillating stag-circuit shorts like After the Ball (1897), and the proto-horror films Le Maison du Diable (1897) and Robbing Cleopatra’s Tomb (1899).

.

.

Méliès’ work provides the bridge between the show business of one age, the theatre of belle époque Paris and the Victorian era stage fantasia, and the oncoming time of cinema. Illusionism was Méliès’ stock in trade, but it wasn’t just his love of theatrical stunts and sleight-of-hand that would influence his drift towards spectacle and the realm of the fantastic. His was a genuine love for and affinity with such fare, particularly what was called the “féerie” on the French stage—pageants and spectacles based in mythic and supernatural tales, imbued with a light and evanescent quality of transformative wonder, safe for young audiences in their colour, but also dusted with delicate, good-natured eroticism. Méliès captured the essence of this style as he began to specialise in stories exploiting his gift for realising fantastic imagery. In 1899 he made the six-minute Cinderella, an extremely straightforward telling of Perrault’s story. This proved so popular it gained him international clout and international legal problems, as the popularity of his works with pirates became increasingly galling. Under the banner of his production company, christened Star Films, Méliès began work on his most ambitious film to date, spending 10,000 francs and taking four months to create a film over fifteen minutes long. This odyssey was Voyage dans la lune, or A Trip to the Moon, inspired by ideas from Jules Verne’s novella of that title and H.G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon, via, perhaps, Jacques Offenbach’s light-hearted operatic spin on Verne.

.

.

Méliès’ work dated quickly in its day, as the fast-moving tides of technology and taste almost resulted in its total loss, swept away just as CD-ROM and VHS have been in the very recent past. After Méliès fell into ruin and obscurity, his rediscovery came when cinema first started looking back over its shoulder at the past. A Trip to the Moon is so familiar as a totem of pop culture inception today that it can seem near to cliché. And yet it’s as tantalisingly strange, witty, and original now as it was a century ago, a broadcast from the very edges of technological memory and modern reference. Of all the things cinema has been and is now, a seed for so much lies within A Trip to the Moon. It’s an experimental work, feeling out the peculiar textures and tricks of this new expressive form recognising no limits, only a basic set of proposed rules and a governing urge. It’s a protosurrealist’s fantasia mapping out the universe as annex of the interior imagination. It’s a pure auteurist relic created by a man who tackled and manipulated every aspect of his burgeoning craft. It’s a work of spectacle driven by special effects and a desire to wow an audience with visual impact. It’s a spry and funny burlesque on the themes of genre fiction and the stuff of official mythology, as well as the new, exciting, more than slightly terrifying concepts of the age of mechanisation and expanding consciousness marking the end of the Victorian era and the onrush of the new century. Sixty-seven years later, humankind would actually pull off the adventure Méliès conjured.

.

.

A Trip to the Moon commences with a gathering of astronomers. The presiding Professor Barbenfouillis (Méliès himself) proposes firing a manned projectile to the moon with a giant gun, much to the excitement and consternation of his fellow scientists. A rival argues with him, plainly decrying his plan as preposterous, an exchange that devolves as Barbenfouillis tosses papers and paraphernalia at his adversary. Others agree to the proposed expedition and the mad-bearded professor shakes hands with them. Like much of the film, this scene seems very simple, with the unmoving camera, the stage-pageant sprawl and mime-show action. And yet it’s stuffed full of allusions, sign-play, and waggish jokes. Méliès depicts not contemporary scientists in the strict, professionalised garb of Victorian science but as medieval alchemists sporting cloaks decorated with celestial objects. Immediately apparent in this vignette is the way sexuality becomes a refrain, and above all show business itself; A Trip to the Moon is a paean to its own evocation of showmanship as a triumphant value. Cute stenographers write down the scientists’ every word, and a line of trim-waisted chorus girls enter to give the senior scientists the gifts of telescopes, which then transform into stools for them to sit on.

.

.

This fillip of visual humour has resonance, suggesting the way wonder is often transmuted into stolid function: these men are used to romanticising whilst sitting on their equipment, and their journey is glimpsed as something of a Quixotic tilt not merely at exploration but at regaining lost youthful pluck. Méliès surely hadn’t read any Freud and yet the phallic note in those telescopes is insistent, and recurs later when the chorus girls are needed to help fire off the gigantic cannon. The opening tableau pictures the scientific realm as a cabalistic enclave with roots in weird esoterica and antisocial elitism, but pointing the way forward with industry and inspiration. Perhaps there’s some hint here of the filmmaker’s cunning in regards to his audience’s understanding of forces rapidly changing their lives, an aspect that complicates the film’s usual characterisation as an epitome of an early twentieth century statement of bold forward-looking. Of course, Méliès is also aware that his very film itself is part of those transformative forces, and the very last shot conflates Méliès’ mastery of his new art and the act of heroic discovery. Barbenfouillis’ sketch on a chalkboard becomes great undertaking, as witnessed in the second and third tableaux, as they have their projectile built and great gun forged. The scientists immediately set about modernising themselves, changing out of antique gear into the clothes of Montgolfier-era gentlemen adventurers. Barbenfouillis and his cabal inspect their brainchild’s realisation in the second tableau, but the savants are out of place in this workaday environment, as one man trips over a tub to the great amusement of the workers.

.

.

If A Trip to the Moon repeatedly envisions scientific endeavour and venture into branch of show business, these scenes carry a hint of Méliès’ respect for the process required to produce anything wonderful, as the painted backdrop behind the projectile recognisably reproduces Méliès’ own studio. But the arts of Victorian metallurgy and industry become mere cardboard and paintwork. A Trip to the Moon revisited ideas Méliès had first explored in his whimsical 1899 work An Astronomer’s Dream, which had similarly envisioned an arcane concept of a skygazer dreaming of star-riding nymphs and a frightening moon with a man’s face that at one point eats the dreamer hero. A Trip to the Moon reordered these touches into a more elaborate edition, with the film’s famous central image quoting but also inverting the vision Méliès had offered three years earlier, as a product of human labour careens into the eye of the man in the moon. A simple inversion of a personal joke, certainly, but also an idea that reflects a changed attitude. Suddenly, humankind is no longer so at the mercy of the universe’s caprices. An Astronomer’s Dream betrays a certain level of anxiety filtered through comedy, a sense of the world just beyond our ken as both enticing and threatening. The promise of A Trip to the Moon has been the key promise of cinematic scifi ever since, that wisdom and applied intelligence might turn threat into triumph. The dreamer has become warrior with the way of things. And yet, of course, the aura of dreamlike plunge and the image of the cosmic feminine remain powerful in A Trip to the Moon.

.

.

Seven years had passed since the first time Méliès saw a motion picture. Cinema was coming together with Promethean fire, and still only a fraction of the distance of the path it would travel. To watch the earliest fragments of moviemaking, the work of Edison, the Lumieres, and the handful of other pioneers in the field, is to stare at the very liminal edge of any sense of the past in motion, and the fleeting illusion of human subjects caught in a moment of life, like some form of spiritualism. How much it would evolve again in the following decade and a half, in terms of the techniques of visual storytelling, shifting from Méliès’ mostly fixed camera to the aggressively mobile and expressive camera of the likes of D.W. Griffith and his generation. Méliès brought a school of illusion from the stage to the screen with the essential presumption that one could be used like the other. To him, the camera was conjuring device and an imaginary audience member in his beloved Théâtre Robert-Houdin beholding the wonders he and his creative team could parade before it. Lack of worry about where the camera was and what it was doing at least freed him to labour on his other effects, as the hand-painted settings and props sprawl across the screen, creating an alternate reality, mysterious, beautiful, protean.

.

.

Whilst the film presents only 17 apparent shots with a resolutely rectilinear perspective, it consists in fact of many more: Méliès’ camera passivity is another, carefully controlled illusion. One irony of passing time is that today with many filmmakers competing to outdo each other in masking their technique in elaborate tracking shots and the like, Méliès’ efforts in creating an illusion of sustained reality from a rigorously direct perspective feels less antiquated on at least this level. We can also see the jumps in Méliès’ sense of the camera by looking back to Cinderella with its cluttered but also simpler mise-en-scène and basic camera tricks just three years before—here the shots tend to stand back further, but are also more cleanly composed and energetically arranged. The vibrancy of the sets also betrays a more confident sense of what the frame could contain, what the eye could handle zapping down at it from the screen. The film’s third tableau, a shot of the astronomers overlooking the enormous undertaking of forging the cannon, is relatively brief but one of the most fascinatingly realised and visually dramatic moments, with Méliès using forced perspective, plumes of steam and smoke, and streams of liquid metal. This is a direct transposition of a vivid passage in Verne’s novel, revealing Méliès as adaptor as well as free improviser. The basic visual presumption here is still theatrical, but the shot betrays an interest in conveying process, the art of construction and the spectacle of industry in itself, that has moved beyond the tableaux style into something more definably cinematic, a seed for the epic style in filmmaking. Méliès’ shifts from shot to shot come with dissolves, embryonic film grammar giving the film the mobility the camera lacks.

.

.

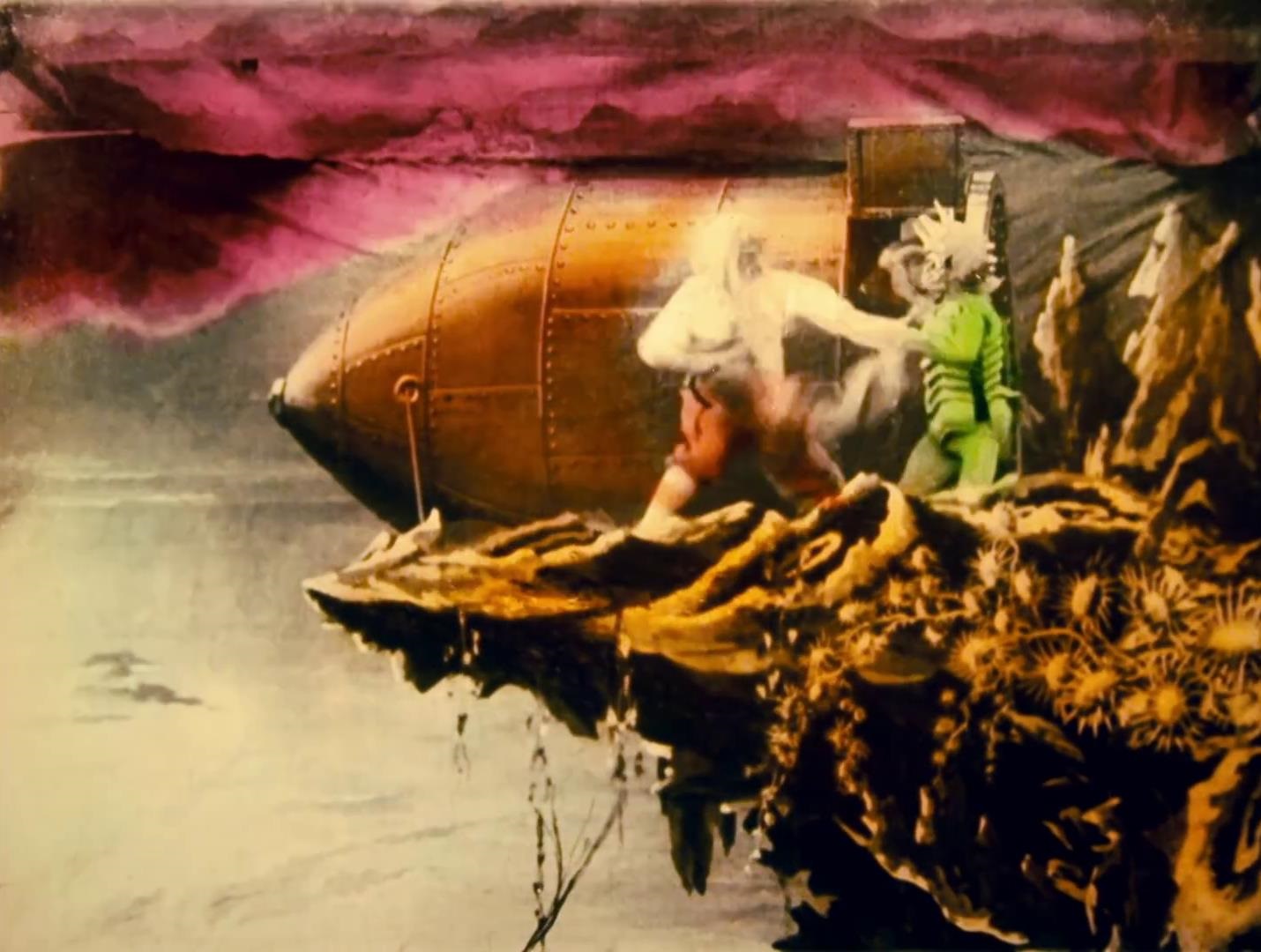

The next three tableaux are the most familiar moments of A Trip to the Moon, indeed some of the most instantly recognisable in cinema history, endlessly excerpted and anthologised as they’ve been. The moon shot project reaches its moment of truth in the midst of public excitement and publicity coup. The scientists climb into their shell and a cohort of chorus girls load it into the great cannon, before a uniformed military officer (François Lallement, one of the Star Films cameramen) signals the gun to be fired. The shell flies through the ether, and the moon, envisioned like an illustration out of a children’s book with man’s face upon its dial beaming beatifically down upon the Earth, receives the interstellar slug right in the eye. These scenes again take Verne’s novel as blueprint, but subject it to a highly satiric attitude. The great business of conquering space is presented not as pure, stoic, Apollonian venture growing out of diverted military force but a carnival of enterprise that mocks martial swagger—the rifle-toting, trumpet-blowing, flag-waving marine entourage are girls who look like a rough draft for Mack Sennett’s bathing beauties (including Méliès’ lover and later wife Jeanne d’Alcy), sending a bunch of old farts to the moon with a gun blast that needs more than a little womanly priming. Méliès’ mischievous take on great nationalist adventures here betrays his background in drawing political cartoons, as well his impresario’s understanding that there is no event so great that can’t be sexed up a bit.

.

.

And, of course, the man in the moon receiving the shell in his eye still blazes with comical and technical genius, one of the greatest sight gags ever to grace celluloid. This sequence utilised Méliès’ technique, pioneered on The Man with the Rubber Head (1902), of approximating what would become the rack or zoom shot (except that the subject was moved closer to the camera rather than the more familiar practice, because the camera was too heavy), to provide a sense of motion. That motion is to give a sense of zeroing in on the moon, which starts off as a vague, mysterious object, charged with enigmatic meaning, then revealed as an animate being who splutters with pain and offence once he gets the iron slug lodged in his brow. Méliès knew well it was a killer image, utilising it as iconography in the film’s last shot and as core advertising motif. Here we seen encapsulated in image and action not just a great piece of humour and a technical innovation, but a pivot of ways of seeing the universe, an idea that legitimises A Trip to the Moon as science fiction and not just playful fantasy. Méliès signals his conversance with a panoply of mythical figures as common motifs in theatrical fancies throughout, and knows his audience is too; the projectile is the hard smack of new scientific possibility right in the eye of a poetic worldview. The idea of landing on the moon is an act of blasphemy according to one unit of values and a simple jaunt to a strange place in another. One irony here is that the filmmaking Méliès was now espousing would soon mostly sweep away the theatrical world he was rooted in, and invent new pantheons of myth to fill in for what he counts as cultural lingua franca. Of course, the tendency of humankind to write its own image on the universe has never really left us. It’s core to understanding some of the most ambitious science fiction films, from 2001: A Space Odyssey’s (1968) depiction of interstellar destiny to Solaris’s (1971) sarcasm towards the notion in encountering the truly alien that can only mimic the onlooker, eternally retarding and frustrating understanding with the collaboration of our most parochial reflexes.

.

.

Méliès offers this vignette as a kind of abstract, symbolic commentary on the idea of landing on the moon, only to follow it up with a different, more literal version of the same thing. The shell actually skids to a halt on the moon surface, depicted realistically as a craggy, brutal landscape, if also, not so realistically, as a place with a breathable atmosphere. The scientists climb out of the shell only for it to slide into an abyss, and, amazed by the sight of the Earth rising on the horizon, they settle down to try and sleep. Méliès revisits the core joke of The Astronomer’s Dream here as the snoozing savants either conjure up the spirits of the ether in their dreams or miss seeing them because they’re asleep, and again Méliès evokes the mystical way of looking at the universe with erotic overtones. The Pleiades look down in bewildered amusement, depicted as a flock of disembodied girls’ heads framed by stylised model stars, the snoozing old men still cheated of their true promised land. The moon goddess Phoebe (played by regular Méliès player and stage star Bleuette Bernon) and irate old Saturn argue over what to do about these interlopers, a fight Phoebe wins: she causes a gentle snowstorm that wakens them and drives them follow their shell into the abyss. The concept of the beneficent cosmic force overlooking sailors on the celestial ocean is, in spite of science fiction’s nominal agnosticism, a constant refrain in a lot of the genre’s screen existence, but Méliès’ sense of humour about the notion is rarer, the contrast of beatific Phoebe and ranting Saturn, who leans out of a portal in the side of the planet bearing his name, pictures the gods as comedy neighbours.

.

.

Descending into the valleys of the moon, the explorers find an exotic and fertile world where strange transformations can occur—Barbenfouillis finds his umbrella takes root and grows into a colossal mushroom. Here Méliès turned to Wells for inspiration, borrowing his moon inhabitants called Selenites to provide plot complication lacking from Verne, whose space projectile had simply rounded the moon and glimpsed the possibility of strange things existing on the dark side. One of the Selenites, weird, crustacean-like hominids fond of leaping bout like acrobats, erupts from the underbrush and intimidates the scientists sufficiently to make Barbenfouillis strike out with another umbrella, causing the alien to explode in a puff of smoke. He does the same thing to a second Selenite, only for a small army of the aliens to give chase and capture the hapless Earthlings. The captives are bound and paraded before the king of the Selenites, who sits on a throne in an alien city, surrounded by his harem of moon maids. Infuriated, Barbenfouillis wrenches at his bonds and snaps them, grabs the king and hurls him to the ground, exploding him, before the humans run for their lives. Méliès provides a sense of propulsion and quickening rhythm here, spurning the languid, dreamy mood of the scientists’ arrival on the mood as the action becomes urgent. Here we have a resolutely linear, comic book-like sense of action as the heroes flee across the frame into different shots, chased by furious Selenites, but not yet offering simple cuts between the scenes, still delineating the change of scene with the dissolve. The result offers a kind of embryonic montage.

.

.

Some have theorised Méliès intended A Trip to the Moon as a purposeful lampoon of imperialist practices and values, apparent in the bumbling but real aggression of the scientists crashing in upon a foreign culture and wreaking havoc. Méliès was probably aware of Cyrano de Bergerac’s own supposed adventures to the moon, part of his subversive method of mirroring absurdity on Earth. Méliès himself had spent time working as a leftist political cartoonist, taking aim official pieties and pomposities, and he had stirred fights in cinemas by explicitly taking a pro-Dreyfus stance with his film about the case. Later, with one of his last epics, Conquest of the Pole (1910), Méliès would be less abashed in poking fun at suffragettes and their opponents. A Trip to the Moon is filled with images smirking at the hoopla of nationalist intrepidity and the idea of timid humans faced with frighteningly wilful organisms. Whilst such readings might easily be taken to unlikely lengths, it is plain Méliès has a lot of fun transposing the template of imperialist-era adventure stories onto the moon, following the same basic pattern as any Tarzan story, but keeping tongue deep in cheek: the explorers tramp into the unknown, are captured by hostile natives and paraded before their overlord who embodies an archaic ideal of lordly domain, before the heroes make their escape. It’s certainly a long way from Wells’ portrait of the Selenites as a sentient race governed by resolutely different social and biological constructs. Blood-and-thunder plotting is, however, viewed through Méliès’ sensibility, the playful, naïve state of early cinema, and the traditions of the féerie, finding comic diminuendo in the fact that the Selenites explode rather than die realistically, and the easy manner in which Barbenfouillis breaks the ropes that bind him. Méliès’ moon bleeds but his Selenites disappear in puffs of theatrical smoke. The universe is alive but life is no more than a moment’s dream.

.

.

Méliès nonetheless dashes with breathless art towards his climax as the scientists locate their craft and climb in, whilst Barbenfouilles labours to pull the shell off a cliff, finally succeeding just as a lone Selenite grabs hold of the shell and is dragged over the edge along with it, plunging back towards Earth. This moment suggests Jack and the Beanstalk as another fairy tale influence on Méliès, another story of a naïve man ascending to a strange land, whilst Méliès abandons any pretence to scientific realism in favour of straight fantasy logic. Méliès has the shell splash-land in the ocean, the only use of any real, outdoor location in the film with the shell and splash superimposed over real waves. The shell sinks into the ocean depths, actually a fish tank, and then is pulled back to shore by a ship—a sliding cardboard cut-out pulling a similar mock-up of the shell, from which a handheld puppet waves a flag of triumph. These effects are obviously incredibly primitive on one level, and yet ebullient in their zest and stirring in Méliès’ willingness to use any and every trick to tell his story in as visually inventive and dynamic a manner possible. Here is the essence of a delight in artifice as its own aesthetic value that many a much later filmmaker, from Terry Gilliam to Tim Burton and Michel Gondry, has embraced. Questions of realism or artifice were probably entirely incidental to Méliès considering the nature of early filmmaking, and yet one can’t help but feel he was the kind to choose artifice every time.

.

.

The scientists make their triumphant return to their homeland with their Selenite captive, who is paraded before crowds and forced to dance, whilst Barbenfouilles is immortalised in statue as the conqueror of the moon, with the slogan “Labor omnia vincit” on the pedestal. Méliès retains hints of his acerbic side here, with an undertone of violence in the scientists’ success—the statue of Barbenfouillis depicts him with boot planted on the moon with the shell lodged in its eye, whilst the Selenite has been reduced to dancing bear. But the overall tone is one of pure elation, an envisioned moment of triumph that codifies all the confidence and joie de vivre not just of Méliès and his filmmaking team but of the young twentieth century itself, just starting to look up not just in fantasy but true ambition. Méliès evokes the masque dance used to end some theatrical performances in celebratory mood, and underlines his work here above all as an expression of carnivalesque joie de vivre, a work that stands above all as a tribute to the very idea of dreaming big. It was an apex of ambition and accomplishment for Star Films. Méliès had drawn on the theatre world he loved to help augment his vision, utilising friends who were singers in Paris’s music halls as his crew of scientists, beauties from the Théâtre du Châtelet as the cannon girls and star maids, and acrobats and dancers from the Folies Bergère as Selenites.

.

.

A Trip to the Moon’s influence is incalculable—every special-effects spectacle, every alien that stalks the screen in every scifi film owes it a debt of gratitude. The influence hardly stops at genre borders either. Edwin S. Porter’s seedling western The Great Train Robbery (1903) would take licence from the film’s shunting film grammar, controlled theatrical viewpoint, and dashing action style, echoing on through a vast array of horse operas and action films. D.W. Griffith would state he owed Méliès everything. The director’s own masterpiece is perhaps a purer fantasy, made four years later, The Kingdom of the Fairies, still just as stagy in some ways but now overwhelming the cinematic frame with shifting planes of vision and effect, and conveying the essence of the féerie Méliès loved so much for cinema’s posterity.

.

.

But it was A Trip to the Moon that made Méliès the most famous of early filmmakers and which will probably always define his contribution. The only problem with Méliès’ success was that it was so inescapable. He had changed the way a very young art form conversed with its audience and expanded its scope to become a zone of pure creative vision, diverting the form away from the Lumieres’ vision of a tool of veracity. He had set in motion processes that would make him the first real movie king and the first to be dethroned by shifting tastes, evolving styles, and the brusque way of business that would soon dominate what turned quickly from enthusiast’s pursuit to heavy industry. Méliès had employed all that his studio and the theatrical world of Paris could offer, but all that was doomed to be swept away or radically transformed by an age of movable entertainment feasts. The century for which he had provided a fanfare would indeed eventually see men land on the moon after times of grotesque tragedy and grand calamity. The flame of grace that still gutters within A Trip to the Moon, in its charming and naïve proposition of the future by way of the past, is that it remembers that moment when anything seemed possible for us. Labor omnia vincit.

When I first saw a version of A Trip tot he Moon on TV back around 1960 0r so, I was fascinated the the whole aspect of fun they seemed to be having all through this film. I was quite young and other than some TV fare and a few Westerns, nothing stuck out in my memory like the moon face with the shell stuck in it. Over the years, I realized I must’ve seen two or three different versions of it, but hadn’t noticed at the time – the general concept and execution of the film was forever stuck in my head, and I didn’t have a problem with that. As I grew up, I continued to have a deep interest in SF and fantasy, which I trace directly to this film. The enthusiasm of the film itself seems to have seeped into your article, and that’s a good thing, I think, it should always be viewed in that light. Excellent article!

LikeLike

The first time I got to see it was a more peculiar setting, Van – it was showing in a loop on a screen in an exhibition of space technology in Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, under a Saturn V rocket exhaust cowling. Not to be forgotten!

LikeLike